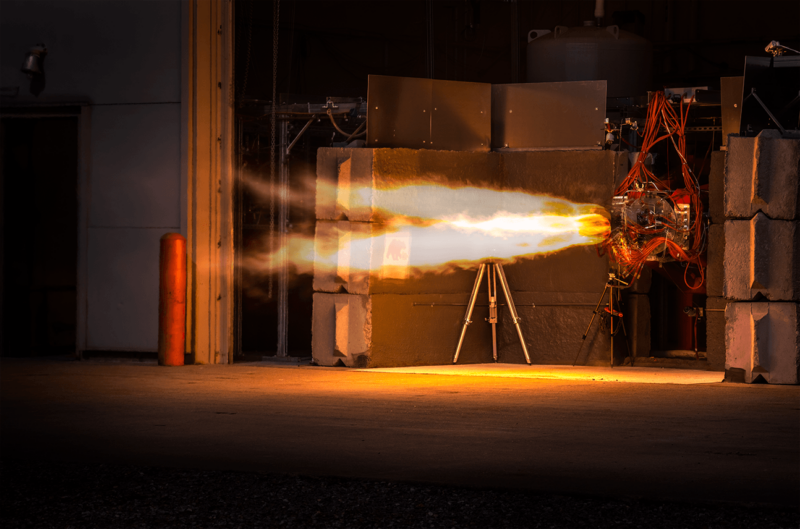

Startup Ursa Major announced Wednesday that it had completed qualification of its Hadley rocket engine for use by both a space launch vehicle and a hypersonic launch system. The Colorado-based company said it has already started delivering flight-ready Hadley engines to two customers, Phantom Space and Stratolaunch, and plans to produce a total of 30 engines this year.

The Hadley engine is relatively small as rocket engines go, with about 5,000 pounds of thrust. At that performance level, the Hadley is comparable to Rocket Lab's Rutherford engine, nine of which power the first stage of Rocket Lab's Electron rocket.

In its announcement, Ursa Major touted the versatility of the Hadley engine being used in two different environments. Phantom Space is developing its Daytona rocket as a small-lift booster, using seven Hadley engines in its first stage to lift up to 450 kg to low Earth orbit. A single, vacuum-optimized Hadley engine will power the upper stage. Phantom says it is booking launches for 2023.

Stratolaunch, by contrast, has built the world's largest aircraft, with a 385-foot (117 m) wingspan. Known as Roc, the aircraft recently completed its fourth test flight and reached an altitude of 15,000 feet (4.6 km). This massive carrier aircraft will be used to launch the rocket-powered Talon-A hypersonic vehicles, which will serve as a test bed for hypersonic research. Stratolaunch plans to begin test flights this year and offer commercial and government service in 2023.

Multiple uses

"It's been quite difficult," said Joe Laurienti, founder and CEO of Ursa Major, in an interview with Ars about developing such a versatile rocket engine. "When you're focused on a single mission, you're focused on a single application. You really narrowly tailor the things that can go wrong on the engine that you have to work out."

As it is intended to serve multiple users, the Hadley engine has undergone significantly more test time, about 40,000 seconds to date. It has been tested in air-launch simulations, for multiple-restart capability, deep throttling, and more. "You try to simulate far more issues that the engine has to go through and survive, than a single mission or a single launch application," Laurienti said.

After previously working on the Merlin rocket engine at SpaceX and the BE-3 at Blue Origin, Laurienti founded Ursa Major in 2015. He saw a lot of launch startups but felt there was a niche for a company focused purely on propulsion. His company decided to start with a smaller engine (because small engines were economically feasible) and then grow from there. The Hadley engine now has multiple customers—the Air Force's X-60A is another—and Laurienti said interest is robust.

Laurienti said his sales pitch when he meets with potential customers is straightforward. "Having an engine off the shelf is going to save you five-plus years," he said. "It's also going to save you probably $100 million. So that's usually a quick, quick conversation."

Ripley, too

With Ursa Major, Laurienti has sought to keep engine costs low by using mass-market 3D printers and by keeping a relatively low headcount. The total number of employees at the company only recently went above 200. To date, Ursa Major has raised about $140 million.

And while Ursa Major started small, the company is already well into development of its much larger Ripley engine. With 50,000 pounds of thrust, Ripley is aimed at the medium-launch market.

"We see Ripley getting on the market here in the next couple of years with a couple of partners," Laurienti said. "And then there's definitely another engine program coming down the pipeline that we're not we're not really speaking about just yet, but hopefully pretty soon."

By that point, Laurienti should have a sense of whether the market is ready to support a commercial space company dedicated solely to liquid rocket engines.

reader comments

125