As the global market for startup investing presses to new heights in terms of dollars invested this year, and deal volume ticks up in several regions, corporations are diving into the action.

Data from CB Insights and Stryber indicate that corporate investors are taking part in deals worth more than ever, even if corporate venture capital (CVC) deal activity is not up uniformly around the world.

The Exchange explores startups, markets and money.

Read it every morning on Extra Crunch or get The Exchange newsletter every Saturday.

In a sense, it’s not surprising that CVCs are seeing the deals that they participate in rising in size — the global venture capital market has trended toward larger deals and more dollars for some time now. But questions lie inside the eye-popping figures: How are corporate investors adapting to a more rapid-fire and expensive venture capital market? We also wanted to know if CVCs are shaking up their deal sourcing, and whether the classic corporate venture tension between strategic investing and deploying capital for financial return is seeing a focus mix shift.

To help us understand the data we have at our fingertips, The Exchange reached out to M12’s Matt Goldstein, Sony Innovation Fund’s Gen Tsuchikawa and WIND Ventures’ Brian Walsh. (TechCrunch last covered CVC outfit WIND Ventures here.)

To help us understand the data we have at our fingertips, The Exchange reached out to M12’s Matt Goldstein, Sony Innovation Fund’s Gen Tsuchikawa and WIND Ventures’ Brian Walsh. (TechCrunch last covered CVC outfit WIND Ventures here.)

Let’s talk data and then dig into the nuance behind the numbers.

A boom in deal value

Precisely measuring CVC activity is interestingly difficult. When we discuss the value of venture capital deals, for example, what counts and what doesn’t is a matter of taste. For example, how to treat the SoftBank Vision Fund. Do deals that it leads that include venture capital participation count toward larger VC activity for a given period of time? What about investments led by crossover funds?

No matter what you choose, aggregate venture capital data will always include dollars invested by non-venture entities. So you do the best you can. CVC has the same problem, amplified. Because CVCs are often participatory to deals, instead of leading them, especially in the later stages of startup investing today, tallying concrete corporate venture investment is difficult. So we proceed in the same manner as we do with aggregate venture data counting, including deals that a particular investor type participated in.

Perfect, no. But it’s consistent, which is what we likely care about more. All that’s to say that when we observe the following deal and dollar data, CB Insights notes plainly that for its purposes, “‘CVC-backed funding’ and ‘CVC-backed deals’ refer to corporate venture capital participation in these funding rounds.”

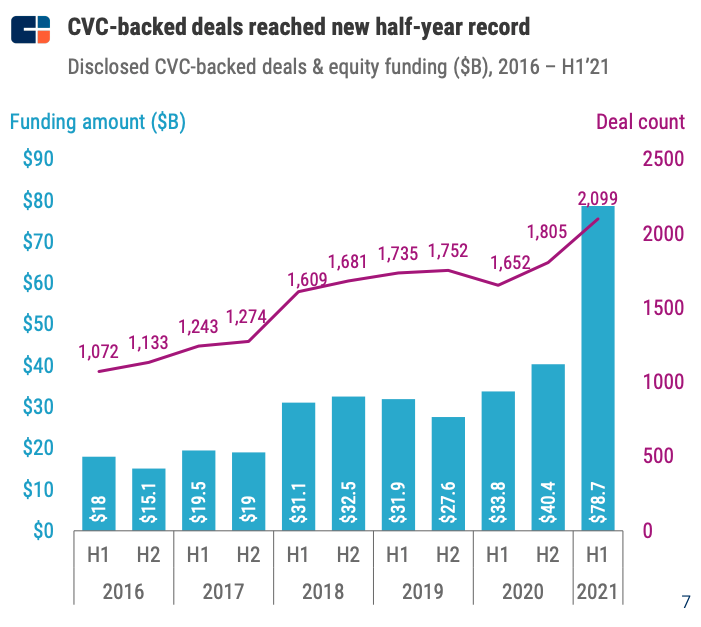

Fair enough. Per CB Insights’ H1 2021 CVC report, CVCs participated in $78.7 billion in funding activity in the first half of 2021, a record for a half-year period. That dollar figure was derived from some 2,099 deals around the world. Precisely how strong those figures are is not clear from their absolute scale.

So, here’s a chart:

The first half of 2021 stands out not just because CVCs took part in a huge number of expensive deals during the period, but also thanks to rising deal volume as well. If we saw deal volume flat and the value of CVC-participated deals rising, we might infer that corporate investors were merely chipping into ever-larger rounds. By seeing deal count rise consistently since an H1 2020 local minimum along with deal volumes over the same period of time implies rising activity levels apart from just rising average deal sizes.

So when we say that global CVC activity appears to be at an all-time high, we are pretty confident that — even with our data caveats — we’re correct. Things are hot in CVC land.

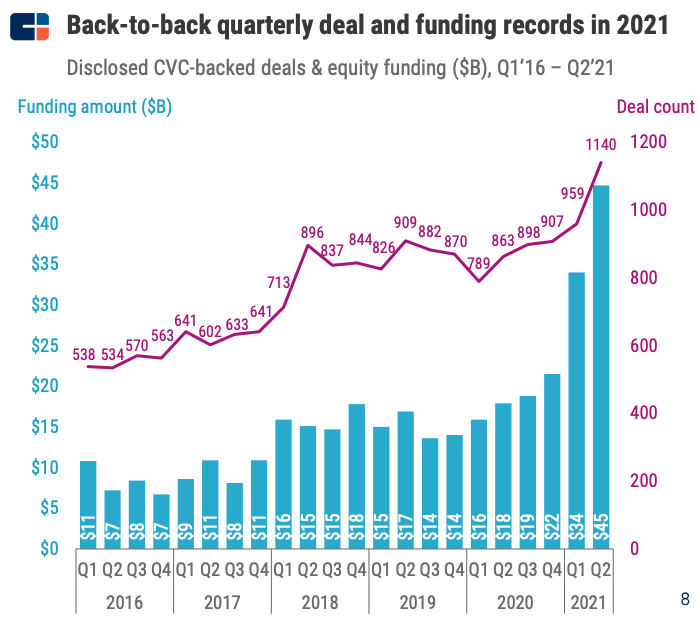

If we zoom in further to a quarter-by-quarter view, the acceleration is even clearer:

From this perspective, we can see that the rising deal and dollar volume of CVC-participated rounds has been present since late 2019 or very early 2020, and that recent progress in numerical results has been steady. Again, this looks more than bullish, even if we make certain allowances.

Some of the increasing dollar tallies of venture rounds that saw CVC participation come from larger deals. Per the same CB Insights data set, the “average CVC-backed deal size grew by 75% [year on year] to an all-time high of $46.9 million” in the first half of 2021. That percentage gain in average deal size outstripped the pace at which venture deals grew more broadly, a figure that came to just 68% across the same time period.

What powered that deal size gain? CVC participation in mega-rounds, or transactions of more than $100 million. Per CB Insights, CVCs participated in some 218 mega-rounds in the first half of 2021. In all of 2020, the number was 184. And 2019’s tally was just 124. Our read of this figure is that CVCs are more willing to buy into ever more expensive venture deals. That’s bullish for startups looking for strategic capital to go along with more vanilla venture equity financing.

M12’s Goldstein agrees, saying that the CVC result data is “skewed by a handful of megadeals and megafunds,” adding that “across the board, the sheer number of participants in startup financing has increased” as well.

Looking at geographies around the world, we can find a series of superlatives. In the United States, CVC activity rose 111% to just under $40 billion in the first half of 2021, effectively a tie with 2020’s full-year result. In Asia, a more modest record of $20 billion worth of CVC-participated deals took place in H1 2021, up from $10 billion in the year-ago period. That’s a record. Deal volume in Asia reached 767 in the first half of 2021, also a record, albeit a very slim one.

Europe was another story of charts going up: CVCs participated in $16.4 billion worth of deals in H1 2021, more than quadrupling the total from the first half of 2020, per CB Insights data. Deal volume ticked to an all-time high of 392 during the two-quarter period.

Stryber, what Europe-focused tech news outlet Sifted called an “innovation consultancy” in a recent post, counted 233 deals with CVC participation in Europe during Q1 and Q2 of this year, worth some $10.4 billion. Again, how you count matters, and we don’t have a take about which group is more correct. But both show rising dollar volume for CVC-participated deals in Europe for H1 2021, even if Stryber shows a modest deal volume decline from recent periods.

Not every market smashed records. Indian deals with CVC participation tied their previous record for dollar value (with H2 2018), but were effectively flat in deal volume compared to recent periods, for example.

Still, the data paints the picture of more and more expensive deal participation from CVCs around the world this year. Now let’s get into the why and how of the changing CVC landscape.

Driving volume

To start, we asked our collection of CVC firms why corporate venture volume was rising. The data is nice, but we wanted to know what the on-the-ground players think is driving the uptick.

WIND Ventures’ Walsh thinks that corporate leaders better understand the “need to evolve, adapt” and lean on external or “open” innovation now than before. In his view, an impact of this better understanding — driven, we reckon, by an increasing pace of technological evolution in many industries — is “more strategic [CVC] going into startups.”

Corporate work to be more open to innovation, including new ideas and tech coming from external sources, stems, in Walsh’s view, from a need to “maintain perceived and actual leadership status,” mitigate a rising tide of “tech-enabled challengers,” and keep up with sector evolution.

CVC activity, then, can be viewed as a plank in corporations’ larger work to stay ahead of the market and fend off competition while keeping their brand as relevant as possible. As CVC efforts can generate positive returns, companies can work on those goals while turning excess cash, perhaps, into extra profitability.

M12’s Goldstein answered the question differently. In his view, corporate and other non-traditional investors “see the ubiquity of software and the necessity of tech exposure, whether it’s for financial or strategic reasons,” perhaps leading to more CVC activity overall. And the investor added that as “four of the six largest companies in the world are tech companies,” it is “surprising” to him “that it took so long for the trend” of “everyone [working] to become a VC” to come into being.

Sony’s Tsuchikawa said that as the world accelerates its digital transformation, “CVC can be a very important and effective tool” in helping “accelerate a company’s involvement and understanding in any rapidly changing environment, particularly when leveraged by emerging and enabling technology.”

Boiling that down a degree or two, Tsuchikawa thinks CVC can be a way for big companies to get both feet into the more fluid startup world so that they can both grok and perhaps take part in emerging trends and tech. That’s always been the case. But if the overall pace of change is accelerating, seeing more companies put more capital to work in the effort makes sense. Tsuchikawa also noted that there are more CVCs than before, which fits neatly into the argument.

Next, we want to understand how CVCs are dealing with the more rapid-fire and expensive venture capital market more broadly.

How CVCs are keeping up

But if everyone is a VC, how to win deals? Goldstein acknowledged that M12 has adapted to the new environment — and was willing to let us know how they are doing it. “We’re pulling every accessible lever here: growing our team, becoming more thesis-driven to identify ‘off the market’ or mispriced deals, and investing in our platform to make M12 an even more attractive investor for entrepreneurs drowning in choice,” he said.

“The changing venture capital market — accentuated by the pandemic — has expanded our geographic aperture,” Goldstein told TechCrunch. This is also correlated to one of the data points highlighted by Stryber and Sifted: The most active CVC investors in Europe are U.S. ones, such as GV and Salesforce Ventures.

Tsuchikawa also referred to his firm benefiting from having access to a broader range of sources, something that might be good news for entrepreneurs. Indeed, it means that CVCs have their eyes open for deals beyond their usual radar.

Perhaps even more of a change, CVCs are making efforts to add underrepresented founders to their pipeline. “In addition to relying on traditional deal-sourcing mechanisms,” Goldstein explained, “we’ve built partnerships with several organizations to realize more diverse deal flow. Black & Brown Founders, Colorintech, Project W and Women in Cloud are all partners in helping us invest more inclusively.”

Another lever that CVCs are using is getting into cap tables earlier than they used to. “With rising valuations,” the Sony Innovation Fund is “increasingly sensitive to our entry point into investment opportunities,” Tsuchikawa said.

Not referring to Sony, but commenting on a higher level, WIND’s Walsh warned that going earlier might be part of unintended risks that strategic investors are forced to take when their value proposition isn’t enough to win deals.

A few caveats

The CVCs we spoke to emphasized returns over strategic goals on balance, which means that our sample perhaps underrepresented CVCs with a more strategic lens. That colors our notes somewhat.

Also, keep in mind that not all data that points up and to the right is great. For non-returns-focused CVCs, for example, exit volume might appear to be an unvarnished good for corporate investors. After all, who doesn’t like faster cash returns on long-term investments? According to WIND’s Walsh, however, there is another perspective.

“Current market conditions are delivering financial returns quicker than expected,” he said, while also perhaps “getting in the way of strategic goals.” How does that work in practice? Per the investor, his firm has “had several exits after writing our first check into a company,” which he admits is “not a bad outcome.” But the money behind WIND, its “corporate sponsor” in Walsh’s phrasing, would “prefer more time before a change of control happens to nurture and work on their own value-add strategic goals for the company.”

CVC: Earlier, faster, but still about the money

It appears that CVC is much like the rest of the venture capital market; it’s returns-focused and making adaptations to a faster, more expensive VC market. By going earlier and spending more, CVCs sound like most traditionally later-stage venture capital that is trying to keep its footing in the VC returns pantheon.

Perhaps this should not be a surprise. We’ve seen non-venture funds flow into the later stages of startupland, pushing VCs toward earlier-stage and more venture-y deals. Why would CVCs be immune to the same trend? And because everyone’s money is green, seeing CVCs move earlier to get deal access is simply logical.

Perhaps instead of drawing a bright line between CVC and VC, we should simply consider all pre-Series C investments to be venture capital, and all deals after that mark to simply be crossover funding? That taxonomy will cause some squawking, surely, but at this point, it feels more honest.